I never expect that the first cultural difference of working between the two countries would focus on bathrooms but this is the Damp Patch.

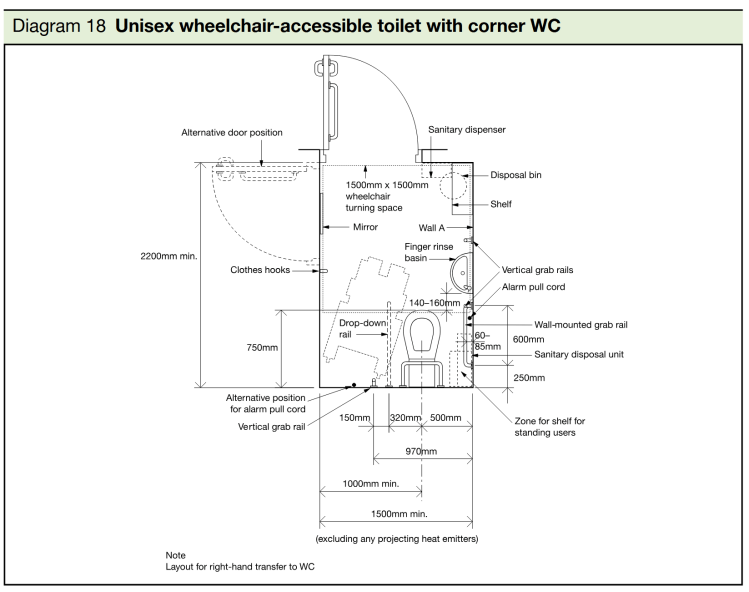

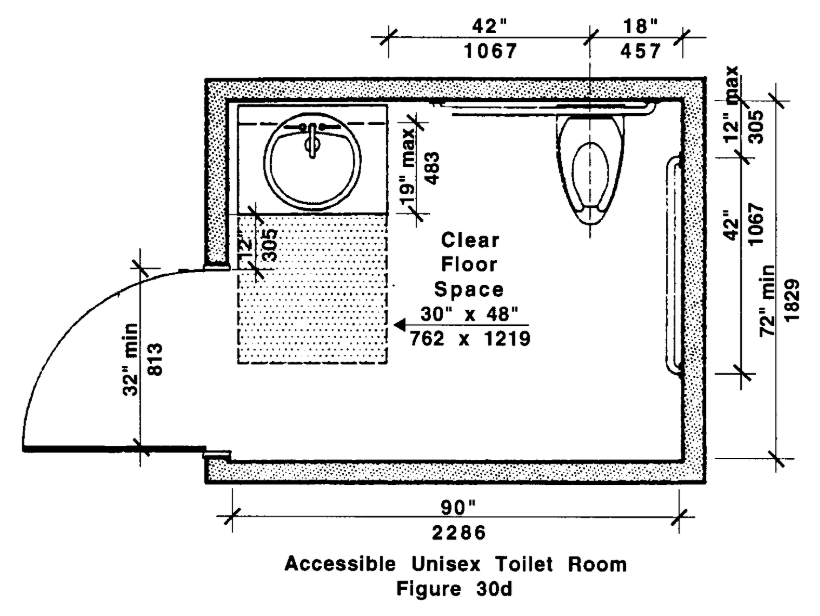

Coming from the UK, where a compliant fully accessible WC is a snug 2.2m x 1.5m (7′-3” x 4′-11”) box of pure function, comparing to my first Massachusetts project felt like an indulgence: a 90in x 72in (2286mm x 1829mm) room that could almost pass for a small bedroom. You can basically swing a cat in it! But the real differences lie not in size, but in philosophy.

In the UK, everything is tightly choreographed. The basin sits within arm’s reach of the WC, perfectly placed for someone transferring or washing hands before repositioning their chair. Its a detail born of necessity, the space is small and every millimeter counts.

The drop down rail to the open side is another quiet triumph of practical design. It gives a user genuine independence and flexibility. I took it for granted until I began working in the US and realised that, under 521 CMR, it simply doesn’t exist. Instead, the grab bars are rigidly fixed: one to the side, one behind. I’ve yet to understand how the rear one truly helps anyone other than to bruise their knuckles!

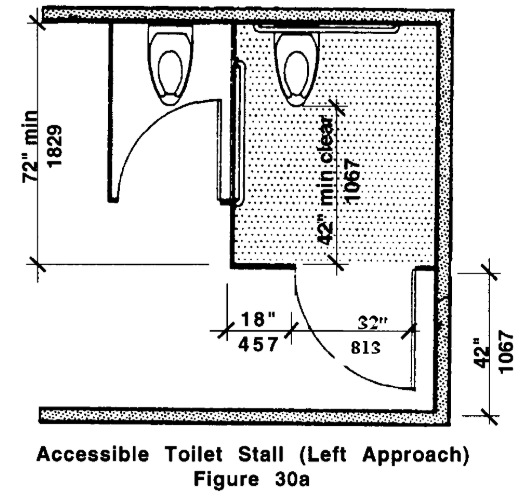

Another key distinction is how the two systems define accessibility itself. In the UK, a building must provide a dedicated, self-contained accessible WC, a recognisable, stand-alone room with its own proportions and fittings. In the US, compliance can often be achieved within a main restroom if at least one stall meets the required dimensions and clearances. Both achieve accessibility, but in very different ways.

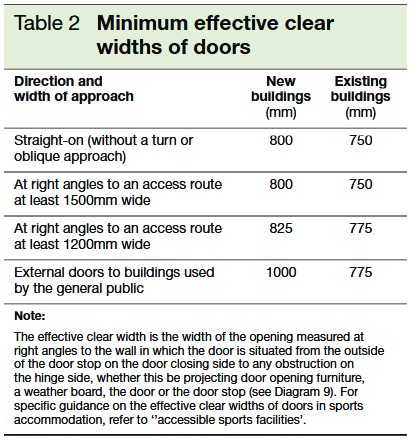

Door clearances tell another story. Both countries require almost the same. 800mm (31.5in) in the UK and 32in (813mm) in Massachusetts, yet the spatial choreography is entirely different. In the UK we only allow outward swinging doors to preserve manoeuvring space inside. In the US, may doors open inwards, prioritising the corridor over the room. It’s a subtle difference, but one that completely changes how a wheelchair user approaches the room.

Nothing captures the divide better than the electrics.

In the UK, a bathroom is practically sacred ground: sockets are banned except for shaver outlets, and even then only beyond Zone 2 per BS 7671:2018. These zones are measured distances from baths, basins, and showers, designed to keep electricity far from splashes.

In the US, bathrooms are dotted with GFCI-protected outlets (see those reset buttons?). They’re near sinks, mirrors, and even beside toilets. It’s a fascinating contrast in risk philosophy: British caution versus American convenience.

Visual contrast is another area where British precision meets American looseness in my experience. In the UK, we follow Light Reflectance Value (LRV) guidance, ensuring atleast 30-point difference between grab rails and their backgrounds. Consider black being 0 LRV and pure white is 100 reflecting all light. It’s a subtle way of making fittings visible to people with low vision.

In the US, contrast is often left to aesthetic preference. Accessibility is measured in inches and pounds, not colo(u)rs and tones. It’s an omission that says as much about regulatory culture as it does about design priorities.

Interesting the roles reverse when it comes to water efficiency. Massachusetts is impressively strict: WCs are limited to 1.28 gallons per flush (4.8L). The UK’s Part G takes a broader approach, suggesting limits but often leaving specifics to voluntary schemes.

So while the British bathroom is spatially efficient, the American one is environmentally so.

If I had to sum up the difference, I’d say the US bathroom is experience-driven; the UK bathroom is compliance-driven.

The American approach is about comfort and perception, generous space, abundant lighting and a sense of calm. The British approach is about precision, meeting the diagram, hitting the numbers and proving inclusivity through layout rather than luxury.

Neither is wrong. Both are responses to context, climate, and culture. Yet I can’t help feeling that the perfect accessible bathroom lies somewhere between them.