Thermal bridging is one of those quiet realities of building science, invisible until it isn’t. It’s the weak point in a wall, floor, or roof, where heat finds the path of least resistance and slips away. Sometimes it’s accidental, a screw in the wrong place. More often, it’s a consequence of poor detailing or a junction that wasn’t quite thought through.

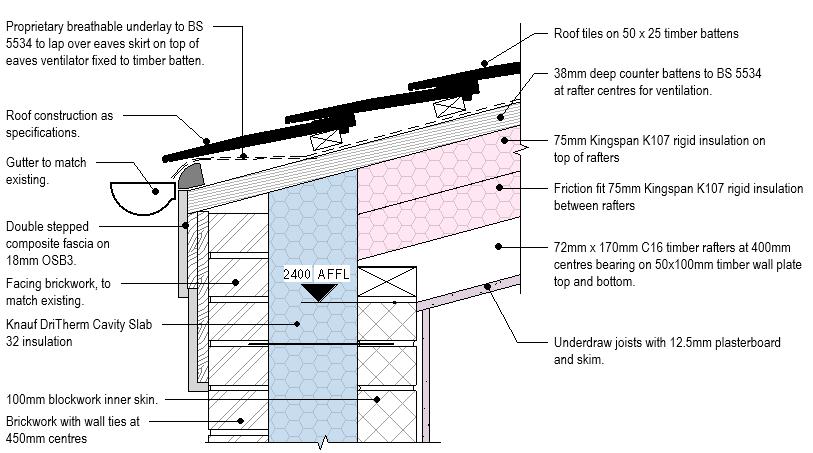

In practice, I’ve found it appears most often where materials or geometries converge: the floor-to-wall junction, the eaves, or around window frames. These are the areas that look neat on a drawing but reveal their flaws when condensation, or worse, mould begins to form.

In the UK, we’ve become almost obsessive about these small thermal leaks. Our regulations demand that we not only acknowledge them but measure them. Every new dwelling requires a SAP energy model, which explicitly accounts for thermal bridges through psi-values (ψ-values), those fractional losses that define the efficiency of a home.

For commercial buildings, we use SBEM (Simplified Building Energy Model) and yes, it is mandatory for compliance with Part L of the Building Regulations. Across the Atlantic, the US is a different phase of the same conversation. Codes like ASHRAE 90.1 and the IECC exist, but most projects still demonstrate compliance through an R-value method; a simple averaging of insulation layers to reach a total thermal resistance.

That’s slowly changing. Some projects in Massachusetts is adopting “stretch” and “specialized” energy codes, which replace this broad-brush R-value method with the U-factor approach already familiar in the UK and Europe. The newer standards consider the real-life interruptions in the building’s thermal blanket and ensure proper detailing.

The difference between the two countries isn’t just how they calculate performance, its in how they build for it.

In the UK, our cavity wall system has long been the unsung hero of energy efficiency. Two solid leaves of masonry with a continuous layer of insulation between. A pragmatic and durable solution. But as regulations tighten, the cavity is widening; from 100mm (4”) to 150mm (6”) in many cases. The walls grow thicker, the sites grow smaller, and the details become more complicated. Even the humble thermal cavity closer is now required in new, wider formats.

In the US, construction has historically favoured the timber stud wall, fully filled with insulation. It’s quick and economical, but thermal continuity stops at every stud. The push for continuous insulation is gaining traction but brings its own set of challenges. Different windows, specialist fixings, high costs, and reluctant contractors make it a slow revolution.

Thermal bridging is rarely felt directly. Most occupants won’t notice the bridge itself, they’ll notice what follows is a chilly patch on the wall, higher heating bills, or worse-case mould. It’s a practical comfort problem, not just theoretical.

In the UK, with higher energy costs and a national focus on decarbonisation, thermal performance has become part of architectural identity. We speak of U-values and airtightness as easily as form and proportion. In the US, where energy is cheaper and climates wildly varied, the urgency differs. Some regions battle to keep heat in, others to keep it out. “Cold bridging” doesn’t quite fit when the challenge might be just as easily be solar gain.

For all its science, the phrase thermal bridging has always felt poetic to me. It’s about connection and consequence. A bridge can unite or it can leak. It can carry the flow of heat, or the flow of ideas between two ways of building.

In my work, I see the literal and figurative bridges everywhere: between cost and performance, between detail and construction, between architect and builder. Sometimes the connections are strong and efficient; sometimes they bleed energy and understanding alike.

To design better buildings we need fewer gaps, both thermal and professional.